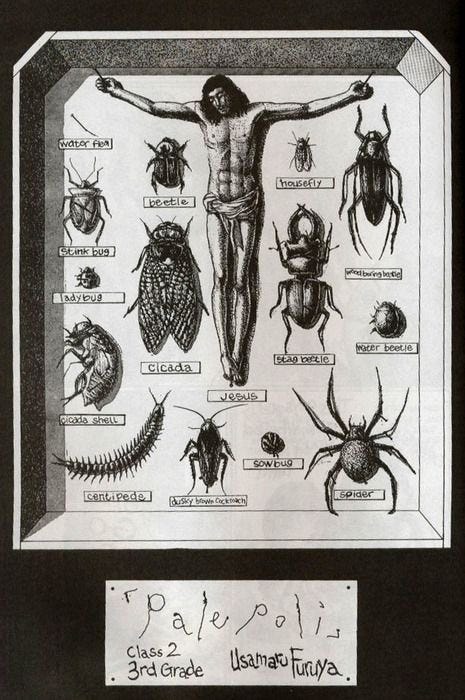

cw/ mild blasphemy? girl idk… i feel like He won’t mind.

When I'm bent over, wishin' it was over

Makin' all variety of vows I'll never keep

I try to remember the wrath of the devil

Was also given him by God

— Mitski, Bug Like an Angel (2023)

I grew up being taught to not fear bugs. In fact, I wasn’t even allowed to be disgusted by them. I’d flinch away from a wasp or a common housefly only to get older eyes rolled at me or scoffing laughter sent in my direction.

“In Nigeria,” my father would often say, “you’d be eating outside and flies would be eating with you. What? So, I should throw away my meal because of an insect? I should run from something I’m bigger than?”

Despite his constant monologuing about his close-knit childhood friendship with bugs, I couldn’t mirror that comfortability. I have a vivid memory of a battle between me and a housefly. Summers in United Kingdom call for ajar windows and overheating fans because of the general lack of air-conditioning in old homes. I was taking a shower, the world blurry without the aid of my glasses only making me even more vulnerable and naked beneath the showerhead’s spray. Then there was a buzzing. Just a slight buzzing at first, just beneath the sound of running water, but my ears latched onto it nonetheless. I cut the water off. The buzzing persisted—the sound soft, soft, then louder, louder still, until it was right by my ear and I was slapping the side of my face with enough strength that it left my ear ringing, my new conch piercing smarting. The buzzing persisted—the sound soft again, soft, then louder until I was flinching and swatting the air by my still-throbbing ear, my still-throbbing piercing. In that instant, I made the executive decision that showering was overrated. I stepped out, wrapped myself in a towel and left the bathroom behind, being sure to shut the door quick and tight behind me to trap the fly inside. Only when my bare-feet hit the carpeted hallway did I register that I was still dripping wet, still covered from neck to ankles in unrinsed Warm Vanilla scented suds.

I was staring down at the puddle I’d created about my feet when I heard someone walking up behind me. My mother.

I didn’t turn around. “There’s a fly.”

“Not even a wasp, or a bee? But a fly?”

“It keeps buzzing near me.”

“This fear of yours…” She walked past me, grabbed onto the bathroom door’s handle. “I’ll kill it for you, but there will come a time when you’re older and you’ll have to face a fly alone.”

I grew up being taught to fear God. Conditioned to fear Him, really. From the womb up until the age of sixteen, I spent every single Sunday in church unless I was sick or I had a major exam the following Monday. Rather than having an inner voice that told me what was right and wrong, an inner voice that sounded anything like me, my inner voice had the same accent as the Pastor. Sometimes it would sound like my mother, sometimes my father, but even when the tone would switch between the three, each voice was a manifestation of the belief that God—this all knowing, all powerful, all seeing, ever-judgmental God—was somewhere out there, watching, not buzzing, never flying close enough for me to swat away. I’d tell a white lie and hear the mother-Pastor-father voice damn me to Hell. I’d get jealous of someone and hear the father-Pastor-mother voice prophesy that I’d amount to nothing as a punishment for that ugly emotion.

Sometimes I’d wonder where in my room He’d most like to judge me from. Did He spread Himself across my ceiling to stare down at me? Did He prefer perching on the laundry basket situated in the far corner of my room? Was He in the closet peering out, no, peering in at me? Or, was He in all those positions? His eyes like reality television cameras, situated throughout my bedroom, my home, my school, the insides of my brain, allowing Him to see each and every angle of my sins? Allowing Him to pause, replay, slow down and time stamp the exact moments that I allowed myself to be led astray?

At my Catholic primary school, I had a teacher who was obsessed with DreamWorks’ The Prince of Egypt (1998) and as a treat to the class she let us watch it one day. I can (and do) watch the movie now and absolutely love it. However, back then the movie terrified me. Absolutely terrified me. It was the first time I’d ever seen a visual representation of a biblical story. Seeing the wrath of God projected on the screen shook me. I watched the scenes of the frogs leaping out of rivers, cattle dying, flies and gnats feasting on human food only for them to get ravenous, uncontrollable, before feasting on human flesh instead. I send the swarm, I send my horde, thus saith the Lord. Despite not being a pharaoh holding people captive, I went home that night and dreamed that the same punishment befell me. I woke up the morning after, my back wet with sweat, my face wet with tears. I clutched my shaky hands before my heaving chest and prayed, prayed for forgiveness. For what exactly? I didn’t know. At the time, it didn’t matter. I would figure it out not too soon afterwards.

I think I was a year or so older when I first realised that thinking about girls as much as I did might’ve been a symptom of that unholy non-straightness that they kept talking about in church. I’d caught it, somehow, maybe, and I had the realisation of that fact on a Sunday. On an Anointing Sunday—the first and/or last Sunday of the month where all members of the congregation walk up to the altar, have the Pastor lay a holy-oil anointed hand on them, pray for them, before they returned to their seats.

I remember realising that I liked girls and sitting in the car, pressed up between my ridiculously long-legged siblings, the radio pumping Igbo Christian music into the crowded space. I remember opening the window for some air because I was feeling queasy, not entirely because of what I now knew about myself, but because my knowing consequently meant God’s knowing, and God’s knowing meant that the Pastor would soon be aware. That’s the thing about Pentecostal churches… they often paint God out as being a bit of a gossip. Anyone “gifted” with the Holy Spirit has apparent meetings with Him where He spills the tea on certain congregation members and then bestows on these preachers the divine authority, the divine right, to tell the rest of the church that person’s business. I was sitting in that car, sick to my stomach, because I was POSITIVE that God and the Pastor had spoken about me. And, if they hadn’t met up for weekly brunch yet, I was sure that the second the Pastor pressed his oil-slathered palm against my forehead, God would give him access to that one thought that wouldn’t leave me alone, the thought of that girl and her smile and her voice, the happiness that she made me feel that was just not allowed.

So, I went to church, walked to the altar, held myself so tight in an attempt to hide my trembling. When I got there, I glanced up at the crucifix and could’ve sworn that Jesus had slipped an eye open just to watch me be exposed to the rest of the church. Nosy, like his father. The Pastor dipped his hand in the oil, pressed it flush against the top of my head, began his short prayer and… nothing.

Hmm.

And then the next month, the next Anointing Sunday… the same thing. Then the next. Then the next. Then my family changed churches, and the months would begin again and end again, and these different Pastors would press their different palms against my same forehead and, still, nothing. I couldn’t believe it. I grew older in the church, gayer, got placed in the choir and went from being a background vocal to leading Worship at the age of thirteen. I would sing every Sunday, get told by older members of the church that my voice was anointing, that my voice “connected them to Heaven,” and I did all of that, all that singing and smiling, while deeply confused. Not about my sexuality, not anymore. Instead I was confused by that image of God I’d been fed, that I’d been taught to fear, that all knowing, all powerful, all seeing, ever-judgmental God that didn’t seem to be mad at me at all.

When I was sixteen and my mother told me that it was time that I started fasting with the adults, this is the reasoning that she gave: “You’re getting older now,” she said, “so you need to pray for yourself, read the Bible yourself. Build your own relationship with God. As your mother, I will pray for you, but there will come a time where you’ll have to face His judgment alone.”

By that point, however, I didn’t really know who He was anymore. I wasn’t entirely sure that she knew Him that well, either.

I will admit, I didn’t absolutely love the books I’m about to mention (you’ll see evidence of that fact in my personal star ratings), but each book explored themes that I chewed on long enough to aid in spitting out this post. Themes of guilt, of the battling old beliefs, and of creating a moral code of your own.

Time of the Flies (2024) by Claudia Piñeiro, Frances Riddle (translator)

Genre: Literary Fiction. Crime.

Pages: 356

Personal Rating: ★★★

After murdering her husband’s lover, Inés doesn’t only leave prison with a fifteen-year absence between her and the outside world… She also leaves prison with a fly in her left eye. Well, it’s not an actual fly according to her doctor, but it flutters in her periphery all the same.

But my little fly reminded me every day that we have two options in life: we can choose to see something, even if it’s irritating, or we can choose to suppress it. And I, Inés Experey, this time, against all odds, want to see.

— Time of the Flies (2024)

Her prison-mate, Manca, is also back on the outside and the two of them start a business together. FFF, “Fumigations, Females and Flies,” a company dedicated to pest control and private investigation services for the women in their local area. However, when one of their clients wants Inés to kill something a lot bigger than a bug, Inés and Manca are faced with the persistent malleability of their own morals.

After reading this book, I went on a wide review reading binge, trying to see how other people have decided to interpret the apparent fly in Inés’ eye. In summary, none of their explanations really resonated with what I felt or what I gathered from the book. The fly in Inés’ eye is barely noticeable when things are going well for her, or when she’s at peace, but it becomes particularly irritating when she’s forced to face her own shortcomings as a mother, as a wife, as a friend or, simply, as a woman. Sometimes the fly gets so large that she can barely see past it. Throughout the book, the reader is constantly lectured about the role of flies. We’re taught that flies are attracted to filth, decay and disease, that they are drawn to the human body (or anything, really) when something within it is rotting. Does guilt not break us down from the inside? Is guilt not, itself, a form of decay?

This book explores guilt and a combative conscience not just through the metaphorical fly in Inés eye, but also through the use of the collective voices of women interspersed throughout. These chorus chapters made the book for me. Overlapping voices, combatting viewpoints of faceless women not only making comments on the actual narrative of the book but also on the role of women, the relationships between women and men, women and their children, and feminism on a whole. Despite the voices speaking as one, they never agree, further demonstrating how the concept of a collective conscience is just that: a concept. Even within movements, individuals are bound to come with their own attitudes, personal knowledge and nuances. It’s not easy to be on the same page with others, let alone with yourself.

Feminism: how we pick each other up. I don’t agree with that definition of feminism, I don’t agree with the image of us as fallen. We’ve fallen many times. We’re falling right now. No, we’ve never fallen down, we’ve been bent, subjugated, flattened, but we’ve never fallen down [. . . ] I don’t agree. Me neither. I do. We have to agree on at least a few basic things if we want the movement to endure.

— Time of the Flies (2024)

Fragile Animals (2024) by Genevieve Jagger

Genre: Literary Fiction.

Pages: 336

Personal Rating: ★★

If I treat myself like an animal, maybe I won’t go to hell either.

— Fragile Animals (2024)

Noelle flees to the Isle of Bute. On her first day there, she runs into a man named Moses who claims to be a vampire. He’s disgusting, awkward, crass yet the two of them develop a relationship based solely on their conversations and their increasingly sacrilegious confessions. Eventually Moses digs deep enough to unearth memories that Noelle has worked hard at running from: her suppressed sexuality, her mother’s affair with the local priest, and the part she played in exposing it.

There’s not a lot that this book did right for me but it honed in on the level of self-disgust that grows within someone who rejects themselves and their desires in the name of religion. How can one possibly stay sane when they’ve been told that each and every one of their thoughts amount to a sin? Noelle has not only betrayed herself but she has betrayed others, people that she swears she loves, all because of the warped moral code that she was taught during her youth, a moral code dictated not just by Catholicism but also by the apparent divine authority attached to her mother’s personal opinions. Religion and her mother’s own teachings are so intermeshed within Noelle’s mind that she, often, sees God and her mother as the same entity, fearing them both, fearing the latter more so.

She used to rub lavender behind my ears before I went to school and in this way I felt that She too was always watching me.

— Fragile Animals (2024)

Noelle spends the whole novel trying to separate herself from her old learned behaviours and beliefs but through her attempt to shed this adopted worldview, she’s forced to confront some very difficult things. This book presents an unflinching character dissection. Noelle is equal parts a victim and a villain. You feel for her, then you hate her, then you’re disgusted at her, then your heart breaks for her, because that’s the thing about doing what you’re told—even when the instructions are from someone else, the actions you do in an attempt to obey them are your own. How do you reconcile with that?

I am a machine that produces guilt more often than it produces words.

— Fragile Animals (2024)

My aversion to insects means that I’m quite paranoid where they’re concerned—I throw pillows at bugs on walls only to find out that the “bug” is just a scratch in the white paint, I step on bugs on the floor only to find out that the “bug” is a clumped up piece of my own hair. When there is a fly, an actual fly, one that I can hear, I pause everything and either gather the bravery to face it head on or I leave the room entirely, keeping the door or window ajar, waiting patiently until the insect decides to give me my space back. The thing about God that makes Him a little more difficult to handle is that I can’t quite place Him. I’m twenty-three years old and I’m still trying to figure it out. If I can’t see Him on my ceiling, on my laundry basket, or in my closet, where is He? And, if the teachings are anything to go by and He’s as big and powerful as the scripture says, how exactly do I squash Him under my heel? Or, more gently, cup Him in my palm? I don’t know what parts of Him, what viewpoints of His, are His and what actually belongs to the humans that have morphed him to better fit around their own views. Honestly, I’ve accepted that figuring that out would be an endless task. Instead, I’ll put energy towards figuring out who or what God is to me and me alone.

Everything has already been written: about women, about flies, about death. The only way to be original is to say the same thing in a different way. When I decide to write something, I’ll start with my own fly, the one that’s part of my body, all mine and no one else’s.

— Time of the Flies (2024)

Here are some Substack posts that inspired this piece…

Time of the Flies was a book recommendation from the amazing

over at Martha’s Monthly. My TBR will never be empty or boring with her around!

The vunerability shown by

in her piece When I Hope in God really urged my fingers onto my own keyboard. She wrote about rage and religion in a way that I related so closely with.

chioma!! this was so insanely beautiful, it’s always such a treat to get your writing in my inbox. absolutely loved the themes in this one & your writing is (as always) such a joy to read !!

I had to set up my account just to comment because I couldn’t leave without expressing this. This was such a beautiful read Chioma. Reading this on a Sunday morning right before getting ready for church makes it all more fitting. I found so much relatability in your words, your thoughts, and even your parents’ comments reminded me so much of my own. At the end of the day, it is definitely all a personal journey and I wish you all the best with yours. 👏🏾👏🏾